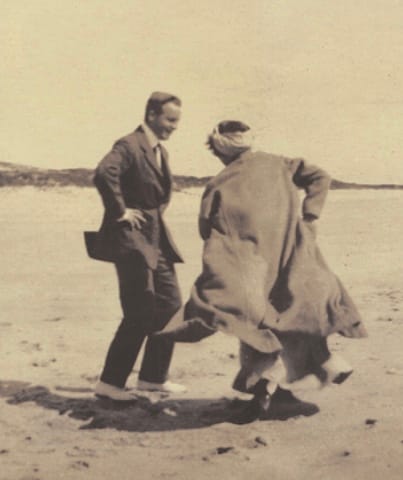

Gerald and Sara

A golden couple heads for France, where wonders and wildness abound. Meet the Murphys.

About a decade ago, I taught a class at LSU Continuing Education about the Lost Generation in 1920s France. I worked really hard on putting it together because I was still stung from my first teaching foray there, which I felt was a bit of a bust. You have no idea how hard I bombed. Determined to redeem myself, I devised a class that was a portrait of a moment between wars. It was chock full of biographies and social and cultural history. In other words, it was a little slice of Paige heaven, served up on a beautiful little platter.

One of my favorite stories from that time is about an American couple who quietly served as the cog in the wheel for some of the Lost Generation's most prominent creatives. The couple was Gerald and Sara Murphy, and the author Donald Ogden Stewart described them thus: "Once upon a time there was a prince and a princess: that's exactly how a description of the Murphys should begin. They were both rich; he was handsome; she was beautiful; they had three golden children. They loved each other, they enjoyed their own company, and they had the gift of making life enchantingly pleasurable for those who were fortunate enough to be their friends."

So let's get to know them...

Gerald was born into a Boston Irish family that owned the Mark Cross Company, which sold fine leather goods. He was a theatrical man and a bit of dandy who was being groomed for the boardroom and his father's business. He never quite felt like he fit in, and his father never did much to help him feel otherwise. But he kept trying. And part of trying, at least for the social set, involved getting into Yale. After failing the entrance exam three times, Gerald was finally admitted, and he decided to go from being the most timid, awkward guy you've ever met to the most likeable guy on campus. He joined a fraternity, and the Skull and Bones society, two things that would set him up to be a certain type of man in life, the very sort of man he didn't feel like he was. Intense, curious and sensitive, Gerald always felt like he had a defect – he had what he felt were curious stirrings for other men, and he wanted to paint, not be an executive – but he would eventually meet a beautiful older woman who would put him at ease. This was Sara. They met while summering at their respective family's homes in the Hamptons, and to him she became this sort of glamorous older sister who could draw him out about his interests, everything from European travel (he had only been once, but longed to go again), to plays, pictures, music and golf.

Sara was born into a family that made its fortune selling printing ink. Toulouse Lautrec used Wiborg Company inks for some of his posters and the company became so successful that Sara's father was a millionaire by age 40. Her mother, meanwhile, was a descendant of General William Tecumsah Sherman, known for burning almost all of Atlanta to the ground during the Civil War. Sara and her two sisters grew up in high society Europe as their father tried to expand his business there. The three Wiborg siblings were known for singing in public in perfect three-part harmony, and charmed nearly everyone they met, including the King of England, to whom they were presented after the turn of the century. For all her high-born allure, Sara was a bit of a hell-raiser, a dangerously curvy girl with creamy skin and golden hair. She not only accompanied the Wright Brothers on an exhibition flight, but steered her own course while sailing – and, well, just living, period. She spoke her mind, which made her intimidating to most men and maddening to her parents. But Gerald found Sara endlessly fascinating, and it dawned on him that she was someone with whom he wanted to create a life. Both came from cold, overbearing families, but in finding each other, they discovered that they understood each other truly and wanted their lives to be full of interesting friends, global travel and stimulating creative pursuits.

"How differently I feel about things seen and done with you," Sara wrote Gerald. "Without you only one half of me enjoys them."

He wrote to her: "Can you see me anywhere, everywhere, and with everyone you'd ever care to see again? This is important. Who is there, after all, with whom you would throw in your lot in life? Are we peculiar? Are we alike? Do we want the same thing? Will we get it together or alone?"

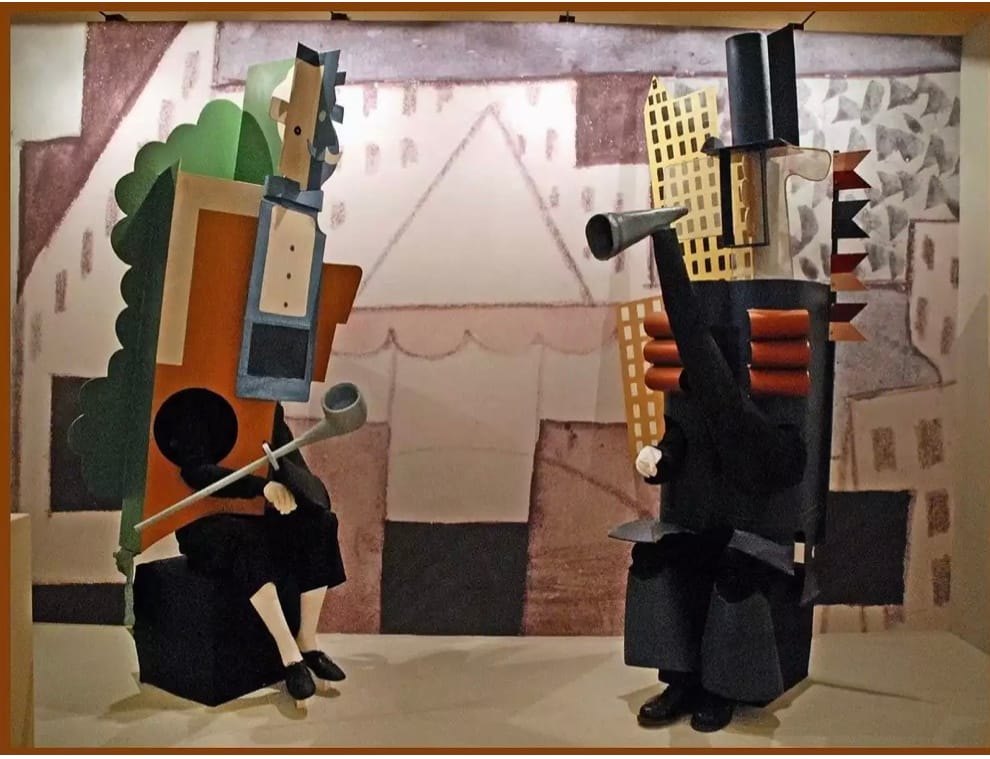

They married against their parents' wishes and soon became parents to two sons and a daughter. Then, they turned their attention to Europe, where the Ballet Russes were one of the most influential dance groups on the continent. The costumes were bold, the dancing was athletic and provocative, the backdrops were unlike anything anyone had ever seen. To Sara and Gerald, Europe felt vibrant and exciting, the perfect place for a young family with the means to forge a new start. Everyone was heading for Paris at that time, and I mean everyone.

Imagine...James Joyce was writing the manuscript that would become "Ulysses" in Montparnasse. Man Ray was dabbling with rayographs. The American photographer Berenice Abbott was also there, as was the dancer Josephine Baker, the composer Aaron Copland, and the novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald. There were wild parties that ended in pillow-fights, and art that felt fractured and chaotic.

Gerald recalled walking past some of Paris' top art galleries one fall day in search of a sale of cubist art, when he saw a set of paintings that stopped him in his tracks. He didn't actually remember what the paintings were, only that he had "a shock of recognition which put me into an entirely new orbit. I was astounded that there were paintings of that kind. And I thought that if that's painting, then that's the kind of painting I would like to do."

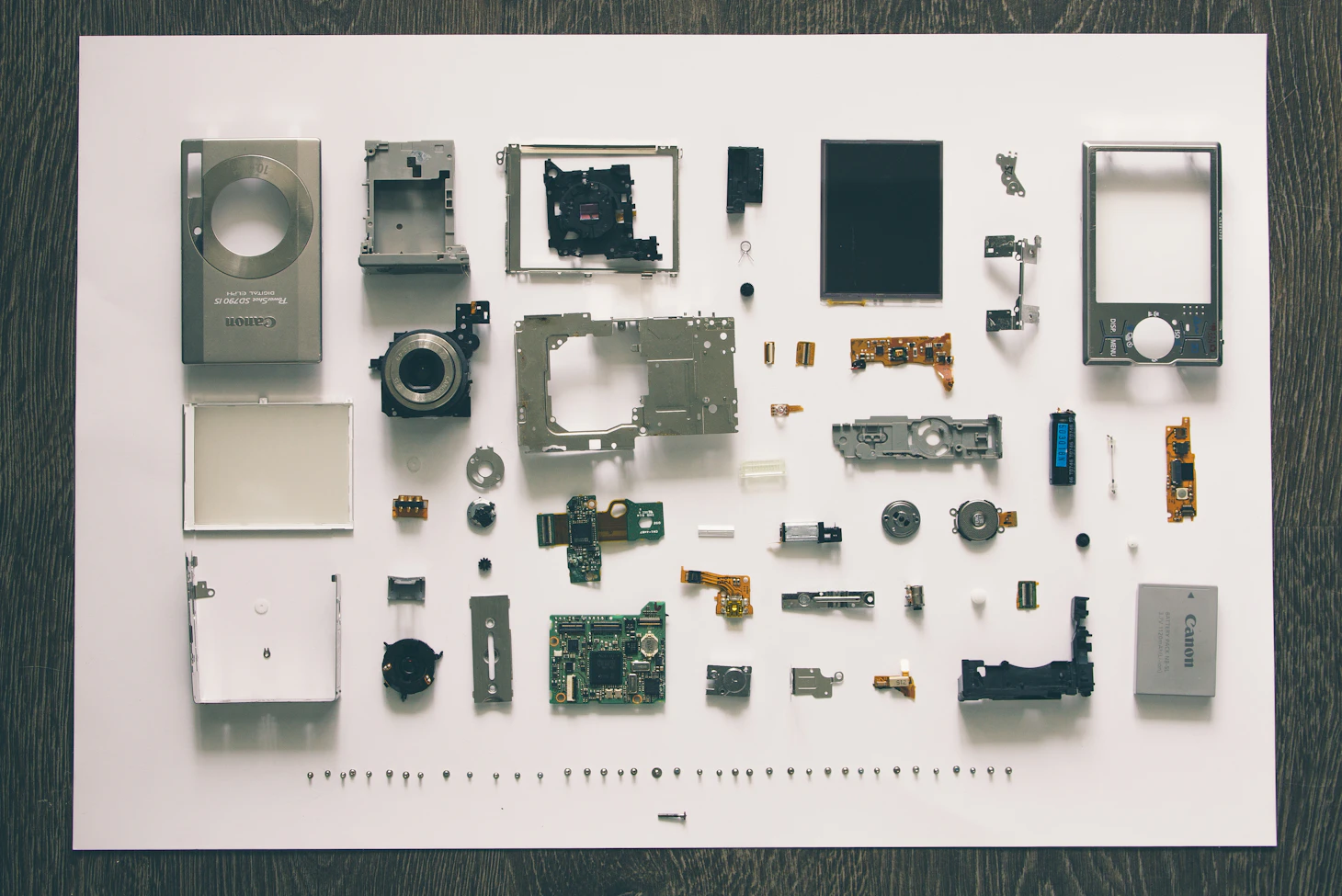

He told Sara about this and she approved. After all, they had the money to support themselves, a nanny to help with the kids, and, now, the desire to study painting in the city that inspired so many of the greatest painters in the world. They found a Russian emigre to teach them, and soon enough they found themselves painting and refurbishing damaged sets for Ballet Russes for free. This was how the Murphys began to cut their ties to a society that they felt stifled them. The work was hard, but fulfilling, and Gerald began branching out to do his own large scale works with close-up views of unknown machines, ocean liners, and engines. Every detail was deliberate and precise, just like the life he and Sara were trying to create for themselves. They would not head back to the United States for some time.

There, nestled in Paris, and the center of a bustling expat life, they sought a summer escape that would allow them to regroup. Their friends Cole and Linda Porter told them about the Cote d'Azur, which was largely deserted in summertime. The Murphys headed south to find a little corner for themselves that they could carve out and make their own. They would find it on the Cap d'Antibes.

More on that next week...

Writing prompt: If you got fed up with the state of things and decided to leave the country, where would you go and why? What would your new life look like?

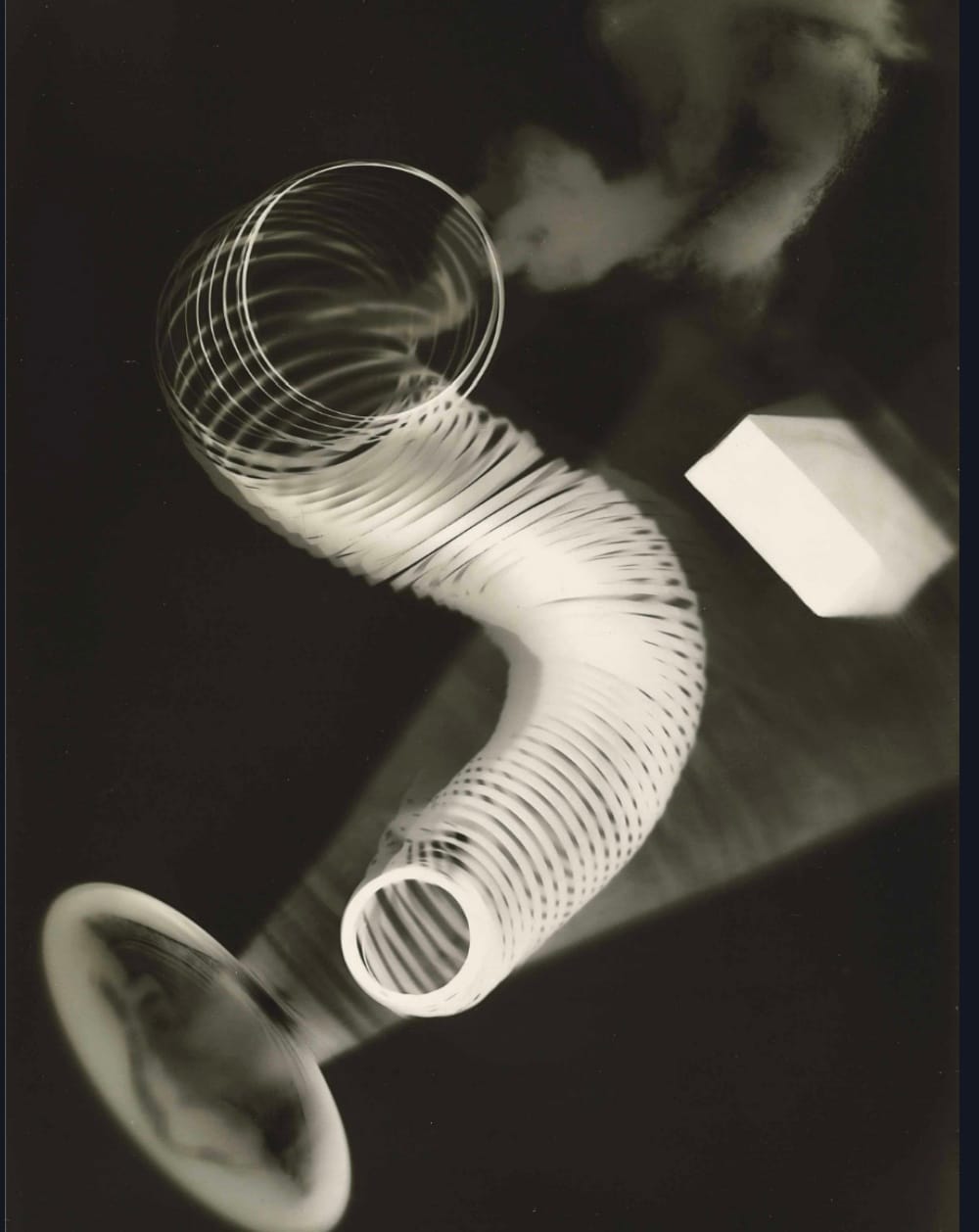

What, pray tell, is a rayograph?

Man Ray didn't invent the rayograph – or photogram – but he did kind of make it his own. The process involves putting ordinary objects (like a spring) onto light sensitive paper and then exposing them to light. The light areas on the print are where the objects have touched the paper and prevented light from exposing the paper. By controlling the exposure of the picture and moving or removing objects, he created images that were unusual and elegant all at once.

"There is no progress in art, any more than there is progress in making love," he said in 1948. "There are simply different ways of doing it."

For all of his experimentation, Man Ray was an exceptional portrait photographer, who took pictures of everyone who was anyone.

Here's one he took of Sara Murphy and her children:

I wish they had smiled, especially because they really had so much to smile about. At any rate, it's pictures like these that funded his more experimental works and helped establish him as one of the more innovative artists in history.

Picasso

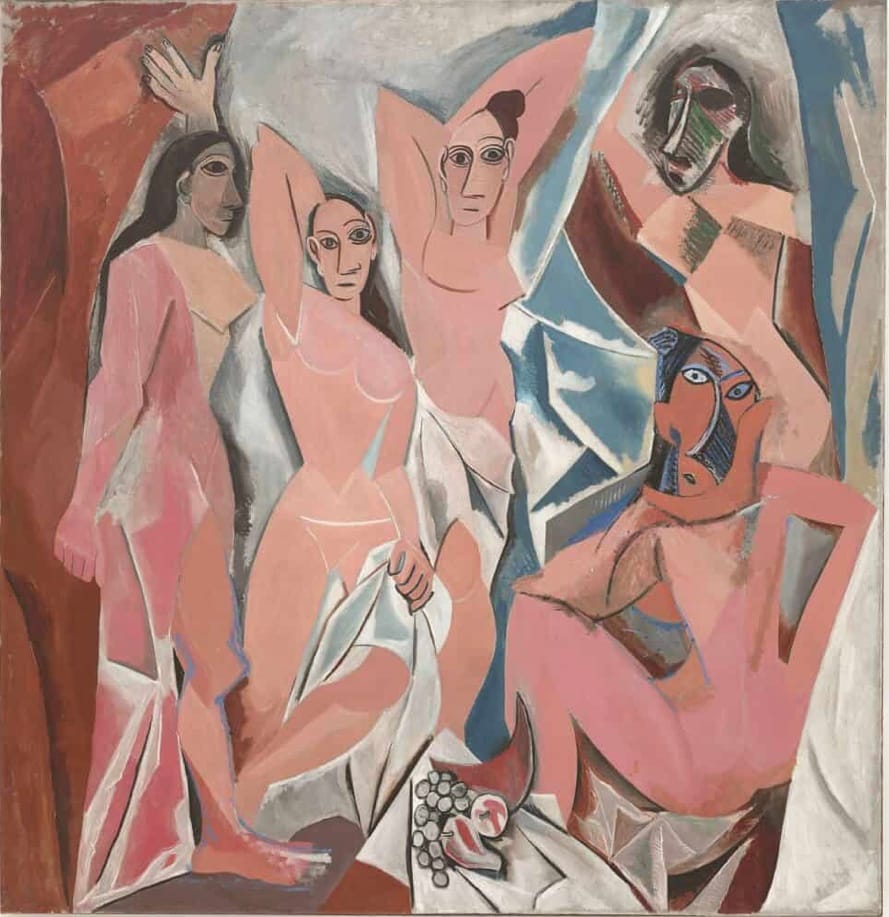

Many of the Ballet Russes sets that the Murphys repaired were created by Pablo Picasso, whom Gerald described as "a dark powerful physical presence who always reminded me of the bulls of Goya." Picasso was reckless and a huge ladies man who usually had several mistresses waiting in the wings for him. But the Murphys just loved him, in part because he changed the way people thought about and created art with one lone painting.

When Picasso exhibited "Les Demoiselles d'Avignon" for the first time in 1916, the painter Georges Braque said it made him feel like he had just swallowed kerosene and was about to spit fire. It wasn't just because Picasso had painted a gaggle of prostitutes. It was that his painting looked like someone had thrown a baseball at the image, shattered it into fragments and then put them back together in strange and menacing ways. People were outraged when they first saw this. It flew in the face of everything they thought a painting should be. But in a society that was changing, especially after a brutal war, it was certainly reflective of the cynicism, confusion and despair people felt. Everything and everyone felt broken, and yet there was still the hope for something better. That's why the Murphys came to France, after all. In doing so they befriended Picasso, whose painting ushered in the Cubist movement that inspired Gerald Murphy to become a painter.

The only real expatriates

By the way, if you were an American in Paris, the only real way to get a taste of what was going on at home was to visit Gerald and Sara Murphy.

"Of all of us over there in the twenties, Gerald and Sara sometimes seemed to be the only real expatriates," wrote Archibald McLeish. "They couldn't stand people in their social sphere at home, whom they considered stuffy and dull. They had enormous contempt for American schools and colleges and used to say that their daughter Honoria should never marry a boy who had gone to Yale. And yet at the same time they both seemed to treasure a sort of Whitmanesque belief in the pure native spirit of America, and in the possibility of American art, music and literature."

You can take the couple out of America, but you can't take the America out of the couple, it seems. Gerald had the drummer in Jimmy Durante's band send them monthly shipments of the latest jazz records from the United States. He also imported the latest home gadgets, which included a waffle iron. I've read some accounts that said the Murphys were the only people in France to have a waffle iron, but I'm not sure how much truth there is to that peculiar distinction. Anyway, they knew all the latest American dances, and read all the latest American books. They were people who loved hosting intimate gatherings of people, because, as Sara said, "there was such affection between everybody. You loved your friends and you wanted to see them every day and usually you did see them every day. It was like a great fair and everybody was so young."

Endnotes

What I'm happy about: Sharing these stories with you.

What I'm looking forward to: Sharing more of these stories next week.

Where I hope you'll donate this week: Room To Read improves reading skills, promotes reading habits among primary school children, and achieves gender equality in education. This non-profit book charity actively collaborates with local villages to establish schools and libraries across South Africa, India, Cambodia, Vietnam, Sri Lanka, Zambia, and other countries so that children can immerse themselves into the bookish world of fantasy and imagination. Please, if you can, donate so they can continue to do this important work.

Next week: What did Gerald and Sara find in Antibes and how did they carve out a space for themselves there?

Paige Bowers Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.