How Dunkirk Brought the deGaulles Together Before France Fell.

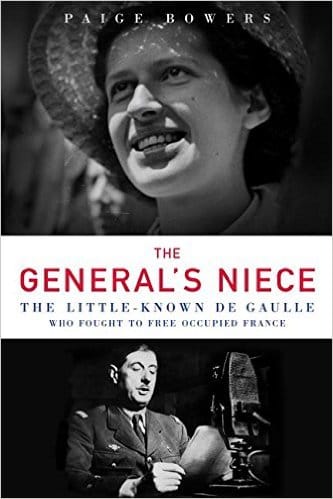

Christopher Nolan’s World War II tour de force “Dunkirk” has captivated moviegoers and reviewers since its release on July 21. It’s the story of the harrowing, heroic rescue of 400,000 Allied troops from the French port city of Dunkirk after German forces stormed into the country. Nolan’s film focuses on the rescue mission itself, not the aftermath in France. In THE GENERAL’S NIECE: THE LITTLE-KNOWN DE GAULLE WHO FOUGHT TO FREE OCCUPIED FRANCE , I write about the havoc Dunkirk wrought on the French population, and how it brought the de Gaulle family together before their beloved country fell to the Nazis. Here is an excerpt:

If there was to be a last stand in France against the German forces that laid waste to the country, some military men believed that it would take place in windswept Brittany. Xavier waited for his marching orders that June in a home that teemed with family members. Armelle, her two small children, Genevieve, and Roger awaited the arrival of Xavier’s frail, eighty-year-old mother, Jeanne, who was fleeing German attacks on the port of Le Havre, not far from where she lived with her daughter, Marie-Agnes; son-in-law, Alfred Cailliau; and their children. Jeanne had been a widow since May 3, 1932, when her husband, Henri, died at age eighty-two. In the years after Henri’s passing, Jeanne’s health had begun to decline too, and she became consumed with seeing her sons before war separated them again.

It was not an easy feat, given the situation on the ground. The German Luftwaffe had begun bombing Le Havre on May 19, 1940, and continued their attacks for the next two evenings. British troops fired antiaircraft guns as Nazi planes dropped bombs on warehouses, factories, shipyards, and Le Havre itself. When large numbers of Dutch and Belgian refugees began arriving in the town by train, locals panicked and thought that the Germans were winning. A dark mood descended over the public as air-raid sirens became commonplace.

The bombing continued in June when the British began evacuating at Dunkirk. Not all troops could be rescued, so they escaped to other ports along the country’s northern coast, striving to find a way back to England. Nazi planes tried to prevent their return by bombing Le Havre ten more times. Bedlam ensued as local officials tried to evacuate residents. Many wanted to flee incoming Nazis by heading for Brittany, but trains could not long travel in that direction because they had to go through the train station in Rouen, which was almost sixty miles to the east. That station was closed, but Jeanne was so determined to see her boys that she traveled 475 miles south to Grenoble to see her son Jacques before getting one of her grandsons to drive her 571 miles north to see Xavier.

After Jeanne’s arrival in Paimpont, nineteen-year-old Genevieve comforted the delicate old woman, whose anxiety gave way to vivid memories from her girlhood of France’s humiliation by the Prussians at Sedan in 1870. She felt like she was reliving those dark days, and her weakened heart couldn’t bear it. Her granddaughter reassured her that it wouldn’t happen like that, not again. Charles would come to visit his mother and Xavier’s family en route to London, where he’d meet with British prime minister Winston Churchill on June 15. After that visit Genevieve assured her grandmother that France would fight back — yes, right there in Brittany.

Brittany. The very shape of the peninsula on which the French army hung their dwindling hopes jutted out toward the English Channel and Atlantic Ocean like the hand of a drowning man begging for help. Two weeks before Petain’s radio address, the military devised a plan that would gather forces along Brittany’s Rance and Vilaine Rivers to fend off an enemy assault. As French troops kept up a stiff resistance along those rivers, allies from Great Britain could stream through the ports west of that line of defense to come to the country’s aid. A prolonged fight under this strategy would allow France to keep its lines of communication open with its allies and, in case of trouble, make it easier to relocate the state’s armed forces and government ministers to London or North Africa.

Two days after Petain addressed the nation, Charles de Gaulle, who had been recently appointed undersecretary of war and national defense, held secret meetings with commanders about the feasibility if this scheme. The overwhelming consensus: Such resistance was futile. There were simply not enough troops to hold off a German advance. General de Gaulle bid farewell to his wife and children. He was headed to London, he told them because things were very bad.

“Perhaps we are going to carry on the fight in Africa,” de Gaulle told his wife, Yvonne. “But I think it more likely that everything is about to collapse. I am warning you so that you will be ready to leave at the first sign.”

The signs were everywhere. After securing passports, Yvonne and the children left on June 18 to join Charles in England.

On the morning of June 18, Xavier de Gaulle and several other reservists were ordered to march west in an effort to regroup against the enemy. His family joined him on the crowded streets in an procession riddled with anger, shame and fear. All around them there was a growing feeling that whatever came next would be in vain. Genevieve lingered close to her grandmother, “this little old lady, dressed in black, so tiny and easy to miss,” so she didn’t fall behind and get lost in the crowd. Throughout the day the young woman reassured the matriarch, as she worked through her own tormented emotions about this turn of events.

By evening, they had walked forty miles to the town of Locmine and faced their first Nazi soldiers. They looked like war gods, Genevieve thought; their smart black uniforms and chiseled features exuded strength and pride as they breezed past on motorcycles and tanks. Some reservists cried because it was clear that there was no hope left and no will to fight this aggressor. As the crowd grew numb with dismay, a priest ran toward them from the other side of the town square. He was excited because he had just heard a French general speak on BBC radio.

“He said we may have lost a battle,” the priest cried, “but not the war. The general’s name was de Gaulle.”

Thrilled by the news, Jeanne de Gaulle, broke from the crowd and ran to the priest.

“Monsieur le Cure, that’s my son!” she cried as she tugged on the sleeve of his cassock. “That’s my son! He’s done what he ought to have done!”

A country away, Charles de Gaulle couldn’t have known how his mother reacted to his decision to offer France another way, but Genevieve remembered the moment as one of her grandmother’s last great joys. For Charles, it was a lonely affair, because as he heard himself speak into the BBC microphone, he realized his life would never be the same. Up until then he had been devoted to both the army and the nation he served. And yet he was not the sort of man to capitulate, which was why he had broken with his superiors and headed to London, to condemnation. At forty-nine years old, fate had lured him away from all his predictable patterns and responsibilities. He was obligated to the France he once knew, and he summoned his countrymen, uncertain of who might hear or put their trust in him.

Few people caught the general’s broadcast, but the ones who did began risking their lives to spread his word.

Excerpted from THE GENERAL’S NIECE: THE LITTLE-KNOWN DE GAULLE WHO FOUGHT TO FREE OCCUPIED FRANCE, published by Chicago Review Press. Copyright 2017 by Paige Bowers. All rights reserved.

Paige Bowers Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.